View Our Collection

Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum preserves, builds and presents its art collection to stimulate reflection, inspire imagination and advance awareness of Ireland's Great Hunger and its long aftermath on both sides of the Atlantic.

Works by noted contemporary Irish artists are featured in the museum’s permanent collection including internationally known sculptors John Behan, Rowan Gillespie and Éamonn O’Doherty; as well as contemporary visual artists, Robert Ballagh, Alanna O’Kelly, Brian Maguire and Hughie O’Donoghue. Featured paintings include several important 19th- and 20th‐century works by artists such as James Brenan, Daniel Macdonald, James Arthur O’Connor and Jack B. Yeats.

Our online collection database is currently a work in progress and undergoing constant updates.

To request use of images from the collection, please fill out the form below:

Deep dive into the museum's collection

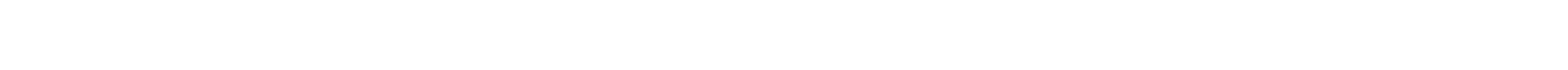

Famine Mother and Children

Artist: John Behan

Date Created: 2000

Medium: Bronze

Dimensions: 23 x 9.5 x 4 in.

Object #: 2000.4

The following was written by museum docent Dr. Maura Stevenson.

The Artist:

John Behan is an Irish sculptor. He was born in Dublin in 1938 and currently lives and works near Galway. Behan studied and trained at the National College of Art & Design (Dublin), Ealing Art College (London) and the Royal Academy School (Oslo). He has received many honors and is a member of the Royal Hibernian Academy. Additionally, he has completed several significant commissions including The Famine Ship at the United Nations Plaza in New York City, the National Famine Memorial in County Mayo and Megalithic Memory in Dublin.

Famine Mother & Children is one of several works by Behan in the collection at IGHM.

The Piece:

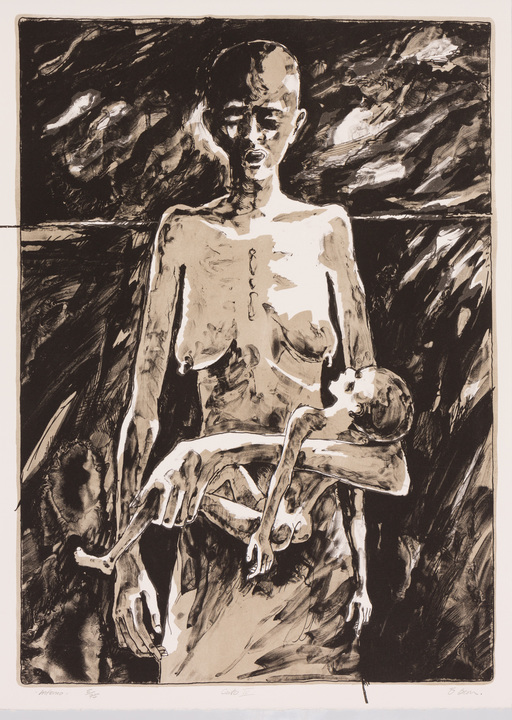

The inspiration for Famine Mother & Children was the image of Bridget O’Donnel and her children. Bridget’s story and an accompanying illustration (attributed to James Mahoney) were featured in The London Illustrated News on December 22, 1849. Although the image of Bridget O’Donnel and her children has become iconic of the famine years, the image was based on a real woman with a traumatic story to tell about her experiences during the famine. Behan’s piece is a 3-dimensional representation of and tribute to Bridget and her children. The sculpture captures the gaunt faces of its subjects, their tattered clothing, their shoeless feet, and their starved bodies.

Bridget lived with her husband and their children in County Clare during the time of the famine. In the interview, she described a man named Dan Sheedey who ordered her family’s harvested corn to be taken from them and later sold in Kilrush. None of the money from that sale went to Bridget and her family, who desperately needed it. Sheedey and his men also demanded that the family give up their cottage. Bridget refused to give possession of the cottage noting that she was 7 months pregnant at the time and sick in bed with the fever. Sheedey and his men were tearing her house down around her when her neighbors came to carry her away, calling for a doctor and a priest. Having been anointed by the priest, her child was stillborn after 8 days and her 13-year old son died from starvation and fever.

The fate of Bridget and her family after the interview remains unknown.

Publication of journalistic interviews was unusual at the time. Publications seldom featured human-interest stories and less frequently detailed the struggles of the poor. Not only was Bridget named in this story, but her story was read internationally and helped people around the world to know and understand what was taking place in Ireland during the time of the famine.

An Gorta Mór

.jpg)

Artist: Robert Ballagh

Date Created: 2012

Medium: Stained Glass Window

Dimensions: 58.5 x 58.5 in.

Object #: 2012.2

The following was written by museum docent Thomas Kennedy.

Artist:

Robert Ballagh was born in 1943, and after 50 years as an artistic celebrity and outspoken activist, he remains active at his studio in the Northside of Dublin. An Gorta Mór was commissioned for the museum’s opening in 2012.

Ballagh’s formal artistic training includes a stint as a student of Michael Farrell, an iconic Irish artist well known for his critique of British occupation of Ireland. Aspects of Ballagh’s style and his sentiments were likely influenced by those beginnings. Although the scope of his work is quite broad in its subject matter, it was his skill as a portrait artist that made him into an Irish icon. Ballagh’s portraits include notable historical figures such as James Joyce, Oscar Wilde, Patrick Pearse, Bernadette Devlin, and Bobby Sands. Ballagh has designed more than 70 Irish postage stamps, largely commemorative, featuring historical Irish events and figures. Ballagh also designed the last series of Irish banknotes before its adoption of the Euro, featuring portraits of James Joyce and Daniel O’Connell. However, his talents extend far beyond the mail and one’s wallet.

Ballagh has been a designer of sets for the stage and, in his pop-art style, a spokesperson for causes and figures in Ireland and worldwide. He has found inspiration in the storming of the Bastille, the Troubles in Northern Ireland, the conflicts in Gaza, the Easter Uprising in Ireland, historical figures and even mythology. You will find his works in museums all over the world and most notably in those in Ireland. Although he is known for his portraits, like many artists he has also included himself in his works. He appears as both the principle subject or an observer or participant in many of his paintings.

Ballagh’s Style:

Ballagh’s style is classically pop art in nature. Where he separates himself from the ordinary is in his devotion and skill for the detail that is ever present in his work. Things like the folds in a shirt or skirt, the unevenness in the fall of the subject’s hair, or subtle shadows differentiate him from so many others in his era. Ballagh also has a great ability to convey messages through his work.This is seen especially in his historically themed works, including An Gorta Mór. If you peer into the faces and postures of his human subjects you will find and feel their being as Ballagh wishes you to experience. Although they are merely renderings you may believe at some level that they are real not simply acrylics on canvas or in this case glass.

Another style variation seen particularly in Ballagh’s historical or mythological works is using the design elements of stained glass in acrylic paintings. Example of this can be seen in An Gorta Mór as well as An Gorta Mórhis works Liberty at the Barricades, Birth of the Irish Republic, and Raft of the Medusa after Gericault. In these pieces even though they are acrylics on canvas they have the outward appearance of a work in stained glass. They are marked by heavy solid black lines separating elements of the work and simplified detail when compared to his portraitures. The realism he seeks still emerges successfully in each piece as he carefully chooses his subject matter and the characters employed to deliver on his themes.

Piece:

An Gorta Mór is the first work that Ballagh produced in stained glass. Some have conjectured that he chose stained glass for its religious roots and Ballagh finds the tragedy of the Great Hunger deserving of these pious overtones. Europe’s medieval churches are full of stained glass windows done in three discrete panels that moving from left to right tell a story. They are called triptychs.

So it is with An Gorta Mór, on the left we are introduced to a typical Irish peasant family toiling in their potato field with evidence of a comfortable though modest home with smoke from a warming peat fire signifying relief from the cold and access to a cooked meal at days end. Nothing lavish or fancy, just a simple life with hard earned rewards for ones labors.

Next we drift to the right and are confronted with the simple potato plant, the life sustaining heart of the Irish peasant of the early 19th century. This particular plant is suffering through an adverse transformation as a result of the emergence of the fungus phytophthora infestans. Phytophthora infestans ravaged the potato crop throughout Europe and especially Ireland in the mid 1840’s and lingered for as long as seven years. Ballagh has illustrated the extreme devastation caused by this fungus and the rapidity with which it destroyed the potato crop by confining the leap from flourishing to foul in a single panel and in fact a single plant. What lies beyond is the subject of the third and final panel.

The tenant farmers and poorer classes in Ireland who depended on the potato as a crucial food source saw their lives alter within the space of a year or two as a result of the agricultural disaster, compounded by the lack of sufficient relief from the British government. The potato was not only a vital food crop, but also a crop that they sold for money to pay rents and to purchase other life necessities. Without it they would find themselves starving, penniless, and when they could no longer pay their rent, homeless as a result of evictions. Ballagh illustrates the plight of these evictions the center of the third panel. The line of those displaced trudging along the road on the lower portion of the panel is one that the newly evicted family in the center must now join to hopefully survive. On the far right of the work we can see ships waiting at sea to carry passengers to begin again in a new land. Two million would travel across the North Atlantic or the Irish Sea at great risk in hopes of finding a new beginning. Some of these people would go by choice, others because it was the only option offered by those who evicted them. One million would never find their way to a ship and perish in their Ireland from starvation and disease while the British government failed them and all of Ireland.

An Gorta Mór vividly tells us this story in three simple panels yet does so in more depth than a simple glance would suggest. Consider the ships resting at anchor in the right-hand panel. They are illustrated entirely in black. By doing so the artist reminds us of the fact that these passages of escape are commonly known as “coffin ships” because of the profound risks and hazards associated with these voyages. In many cases significant fractions of their passengers perished at sea or arrived wracked with disease that would prove fatal shortly after disembarking. An Gorta Mór like so many other art works in Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum subtly educate the viewer far beyond what appears on the surface. It reminds us of the power of great art and the talent of great artists.

Abandonment

.jpg)

.jpg)

Artist: Charlotte Kelly

Date Created: 2011

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 50 x 40 in.

Object #: 2011.11

The following was written by museum docent Mary Cortright.

The Piece:

This is a painting in a series of paintings by Kelly dealing with the tragic realities of the Great Hunger. We have, on a large canvas of stark colors, a human figure far above the horizon. We have a portrayal of a mother and her children - a very different portrayal than many other depictions of mothers and children within the museum’s collection, yet, certainly, no less effective.

This use of stark colors keeps our attention and moves our eyes all around the canvas, as if trying to take it all in as we attempt to define our emotions and we begin to create a story for these unfortunate and unforgettable people. They suffered such emotional and physical pain from disaster, disease, and ultimately death - the realities of poverty, famine and hunger.

This mother, clutching her baby, must be wondering what will become of her two children and herself, knowing they don’t have a chance without her. Alternatively, perhaps the baby has already died and the mother is hanging on in a desperate effort to assure a safe passage with a mother’s love. In their travels they have already seen so many dying or dead by the wayside. Have her other children and husband already died before them and she had to abandon her village, hoping for a different outcome for the living?

The older child, portrayed by Kelly as almost unhuman, clings closely to its mother, already past childhood with a whole life’s worth of experiences in such a short amount of time. Finally, the one magpie is a reminder of impending doom and death, “one for sorrow, two for joy…”

Abandonment represents to me abandonment on many different levels, and, no doubt, more than I have even considered. We see a fence that seems to go on into infinity. Fences keep people and things in or they keep them out. This mother has been abandoned from where she traveled and there is no going back.

Ireland certainly felt abandoned from the English government during those catastrophic Hunger years. Ireland, a Commonwealth of England at that time, was not taken care of, as a parent cares for her children. One million Irish people did not need to die and two million did not need to emigrate from their homeland and, as was often the case, never see their families again.

Children felt the sense of abandonment if their parents died before them or if their parents had to give them to other family members, friends, or even strangers to care for them if they couldn’t.

In some cases, mothers and children were abandoned by the husband and father of the house who went to England for seasonal work and never returned.

Finally, those who emigrated abandoned Ireland and family to seek a better life.

Artist Information:

Charlotte Kelly was born in Galway, Ireland in the early 1960’s and continues to live and paint there today. Although she received a National Diploma in Art and Design from the Galway Mayo Institute of Technology, Kelly furthered her education and became a nurse. In 2005 she gave up her nursing career to concentrate on her artwork. Undoubtedly, her work as a district nurse has encouraged her ability to empathize with those who were in pain and suffering and has enhanced her ability to express herself so passionately and realistically.

Of her art, Kelly has stated:

“Having deep intimacy with the earth and its changing shapes and terms gives a real feeling of spirituality and emotion. Driven by a sense of quietness, these shapes have been molded into a figurative form. Nurturing the work rather than insisting on immediacy. As the poet John O'Donohue wrote:

‘Each tree grows in two directions at once,

into the darkness and out to the light,

with as many branches and roots as it

needs to embody its wild desires.’

I would hope that my work would achieve just that.”

It seems to me that Kelly has achieved all this and more in her work.

Sunset (also known as Rock of Cashel)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Artist: (Henry) Mark Anthony

Date Created: 1846

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 45 x 45 in.

Object #: 2016.4

The following was written by museum docent Joseph McDonagh

Artist Information:

Henry Mark Anthony was a British artist whofocused his talents particularly on landscape painting. Born in Manchester in 1817 to a merchant father, at age six his family moved to Wales. At age 16, Anthony was apprenticed to a doctor who himself was an artist. The doctor encouraged Anthony’s talents, and he soon moved to London and then Paris. In Paris, Anthony came under the influence of the Barbizon School, a group of artists – Theodore Rousseau, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, and Jean-Francois Millet, among others – who were devoted to realism in art.

Anthony became a proponent of plein air painting, or painting done in the field, not in the studio. The great British landscape artist John Constable had also been an advocate for plein air painting, and very quickly Anthony was viewed as Constable’s successor.

By 1860, Anthony’s style of painting was falling out of favor and in that year he failed to be elected to the Royal Academy, stifling his career. Nonetheless, later artists, particularly the Pre-Raphaelites, came to appreciate Anthony’s talents. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the most famous of the Pre-Raphaelites, helped Anthony obtain patrons in his later years. Anthony died in London in 1886.

Background:

Sunset was painted during Anthony’s travels in Ireland, at the outset of the Great Hunger. It is a remarkable painting, in a sense three different paintings at once.

The location, the Rock of Cashel, has enormous national and religious significance for the Irish. Although the current buildings on the site only date back to the 12th, 13th, and 15th centuries, the site is reputed to be the place where Saint Patrick baptized King Aengus, the king of Munster, circa 440-450 AD. This event is seen as the beginning of Irish Catholicism. In 1101, a descendant of Brian Boru (who had been king of all Ireland) gave the site to the Church.

The most notorious event to take place at the site was the Sack of Cashel in 1647. Oliver Cromwell’s army had invaded Ireland and surrounded the village and the Rock. Though many fled, hundreds more sought refuge within the churchyard. The Protestant army refused to negotiate and on September 15, attached the church. It is estimated that between 400 and 1,000 men, women, and children were slaughtered that day.

Piece:

The political and religious significance of the Rock of Cashel would not have been lost on Anthony. The buildings of the Rock of Cashel form the center of the painting. Darkened by the sun setting behind it, one can nevertheless make out the grandeur of the buildings and their magnificence.

The sunset behind the Rock of Cashel is spectacular and vibrantly colored, suggesting something Anthony himself witnessed and painted as it was occurring. Paired with the buildings on the site, these two features alone might have been all that the painting needed.

However, Anthony added something else: The village below the Rock of Cashel. Not only the village, but the village’s inhabitants as well. The sunset behind the Rock obscures the scene below, but close examination shows tragedy. Figures huddled in doorways of decrepit homes, some unroofed. A lonely dog walking the road alongside a mother and child. The figures in the doorways of the homes are barely visible, but they seem to be watching us, watching Anthony perhaps as he stood in the roadway to create this painting. The painting is dated circa 1846. Anthony’s visit to Ireland was at the outset of the Great Hunger, but the disastrous impact was obviously already being felt.

Today, you can of course visit the Rock of Cashel, and you can stand in the same location where Anthony may have painted this picture. The road and the homes along the road are no longer in disrepair, but the Rock of Cashel, 155 years after Anthony’s visit, remains the same.

Basking Shark Currach

Artist: Dorothy Cross

Date Created: 2013

Medium: Basking shark skin, wooden currach frame

Dimensions: 54.3 x 104.3 x 36.2 in

Accession #: 2017.1

In Basking Shark Currach, a one-man currach is stretched with the skin of a basking shark (rather than the usual cowhide). In addition to its skin, fins and meat, the basking shark was once fished for the oil produced from its liver. The fact that a large shark and a currach are about the same size, however, meant danger to fishermen. However, Basking Shark Currach, “the combination of a mysterious animal, generally feared, and the ribs of a small boat have formed a lifesaving relationship. The dorsal fin of the shark reads like the keel of the boat, which is the structure that balances the vessel as it moves through the water”, says Cross.

The question is often asked why it was that people died during the Great Hunger when Ireland is surrounded by ocean. When the potato failed, those fortunate enough to own a currach had to pawn or sell their equipment to buy meal. The winkles and mussels close to shore were soon depleted by starving people.

About The Artist:

Dorothy Cross is an Irish artist. Working with differing media, including sculpture, photography, video and installation, she represented Ireland at the 1993 Venice Biennale. Cross studied at the San Francisco Art Institute, from 1980 to 1982, before eventually choosing to return to Ireland, in Dublin then Connemara. Since the mid-80s her work has included sculpture, photography, video, and installations. She appropriates the locations and materials she uses to make new metaphorical associations that sound out today’s sexual and religious behaviors, habits and identity constructions. She utilizes the animal realm (sharks, jellyfish, cows, crabs, birds, snakes) to question male and female stereotypes and the notions of power, dependence, and fertility. Cross examines the relationship between living beings and the natural world. A sense of place pervades her practice. Living in Connemara, a rural area on Ireland’s wild west coast, the artist sees the body and nature as sites of constant change, creation and destruction, new and old. Her work features ocean and fjord, cave and boat, pearl and fossil, shark and whale. If she embodies any one element, it is water. She also is drawn to found objects. In her hands they alchemize—recognizable, but transformed. Her combinations are challenging, disturbing, and witty.

The Basking Shark:

The Irish word for basking shark is Ainmhí Sheoil – the beast with the sail – and there is also a place name on the south side of the Great Blasket Island where shoals congregate called Gleann na bPéist [Valley or Glen of the Sea Serpent]. When you see dorsal and tail fins of a group of basking shark they are not dissimilar to a long twisting sea serpent.

The basking shark is the second largest shark in the world, only surpassed by the whale shark and is one of the three planktivorous sharks. It is a “kind” shark for divers, despite its size and the impressive mouth that it possesses.

Fishing during the Great Hunger:

When the sea was abundant with fish during the Great Famine years 1845 - 1849, fish was not regarded as real food. There appears to have been no substitute for the food of the common family in Ireland of the time, which was meal or grain for bread and gruel, milk and potatoes. Nevertheless, it adds to the tragedy that when food was so close it was ignored or treated as inferior, or was inaccessible for a number of reasons. Fishing was totally under developed at the time. The remoteness of small fishing communities from any sizeable market, made its commercialization difficult. The historian Cecil Woodham-Smith tells us that our inland shores were teeming with herring and mackerel; while in deeper water there were shoals of cod, sole, turbot and haddock.

Another reason given for the failure to land fish in sufficient quantity to feed the starving people was the frail currach, the most widely used boat for fishing off the west coast. But the rocky coastline with its cliffs, rocks, treacherous currents, sudden squalls, and above all the Atlantic swell, made fishing dangerous in all but the calmest conditions.

When the potato failed, fishermen all over Ireland pawned or sold their gear to buy meal.

The Eviction: A Scene from Life in Ireland

.jpg)

Artist: William Henry Powell

Date Created: c. 1871

Medium: Lithograph

Dimensions: 21.75 x 28 in

Printed and published by Robinson & Mooney

Object #: NA2012.2

Piece:

In this image, we see an eviction scene—the poor, elderly, injured, and ill being turned out of their homes and onto the street along with all of their belongings while the wealthy landlords look on. In the background, we can see homes that have already had their roofs tumbled. The police presence is evident in the men in uniform at the left of the scene. A wide range of emotion is portrayed in the evicted tenants in this scene—one rises in anger brandishing a pitchfork, held back by his wife and child, while another simply sits with his chin in his hands, seeming to have lost hope altogether.

The verses at the bottom of the print were written by Mary Jane O’Donovan Rossa, the wife of prominent Irish Fenian leader Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa. She is known for her poetry for the Fenian newspaper The Irish People, as well as her work for Irish Independence, notably her work raising funds for incarcerated Fenians.

The verses begin describing the village waking to “fear and pain” as the Sheriff and his men approach. O’Donovan Rossa compares the cold of the snow on the ground to the agent of the landlord’s heart as the agent turns everyone, young and old, from their houses and tosses their belongings out onto the ground. A landlord’s agent was a middleman who would manage an estate and any tenants in the place of an absentee landlord who owned land in Ireland but resided usually in England. Agents were known for being ruthless as they had no connection to the land or tenants. Evictions called for by Agents were enforced by local government like the Sheriff mentioned here, or sometimes by the military. O’Donovan Rossa goes on to detail that the people evicted had paid their rent, but were being thrown out despite that because “the Earl wants space for his hunting-ground.” This clearing of land to turn it from tenants to some other purpose is well documented. This was often done to turn the land into grazing for cattle which was more lucrative, but the reasoning given here highlights the feelings of the reasons for eviction being petty or selfish, again emphasizing the heartlessness of those in power during the Great Hunger.

The verses go on to describe how the houses were tumbled, a practice in which the roofs would be destroyed to prevent reoccupation of evicted homes, and how the tenants of those homes reacted. Some “implored for mercy where the name of Mercy had no softening claim”, while others swore bloody vengeance on those who had wronged them. This, too, is documented during the era, with landlords being murdered by the tenants they turned out, perhaps most famously with the murder of Denis Mahon of Strokestown House who was killed in 1847 after evicting all his tenants and sending many to Canada.

The death of the man lying in the center is detailed; he died just before the eviction began and, despite his family’s pleas, his body was carelessly thrown into the street. Shortly after this, his son, the man in military uniform with a fist raised, arrives home from the Crimean War, having just missed his father’s last moments. He says that he has “faced famine, fear and death, to hold aloft the power that gave my murdered father to the grave.” He describes his anger at having fought for England only to return to the ruin they have created in his home and issues a call to revolution to the Irish people, saying that “Celts made resolute and bold” will choose “Liberty or Death.”

While these verses tell the tale of a Great Hunger-era fictional story, the purpose in O’Donovan Rossa’s writing is clear. She and her husband, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, fought for Irish independence in the decades following the Great Hunger and this reminder of the recent suffering of the Irish people would have been a powerful call to arms in the growing Independence movement.

Artist:

William Henry Powell was an American artist best known for his painting of the Battle of Lake Erie, copies of which hang in the Ohio state capitol building and in the United States Capitol. He also executed one of the large historical paintings in the Capitol rotunda, that of the discovery of the Mississippi River. Powell was born in 1823 in New York City, and died in 1879. This lithograph that Powell and Mrs. O’Donovan Rossa may have known each other and collaborated on this work, though as it is a lithograph it is possible the verses were not originally intended to accompany the piece. Powell and O’Donovan Rossa are most likely to have met after the O’Donovan Rossas were exiled to New York City in 1870, where they continued their revolutionary activities in Ireland from abroad.

Inferno, Canto IV

Artist: Liam Ó Broin

Date Created: 2014

Medium: Lithograph

Dimensions: 27.5 x 20 in.

Object #: 2014.4

The following is written by IGHM docent Mary Cortright

Piece:

Unlike many of the 19th century works portraying mothers and children from the Great Hunger, Liam Ó Broin’s modern take is not giving us a sentimental image but, rather, portraying a realistic view of the effects of the Great Hunger on mothers and children. Experts who study trauma tell us it takes five generations to grapple with major trauma such as, but not limited to, famine, holocaust and war. In this work, Ó Broin has certainly dealt with this issue upfront.

When artists paint figures above the horizon they are telling us that this is the subject of their work. There is no doubt in this piece that the subject is THIS mother with child. Artists also often use color to focus our attention and emphasize a point. In Inferno, Canto IV, this artist has effectively grabbed our attention by his lack of color and created a dramatic piece whose image will remain with the viewer long after viewing it.

The title Canto IV refers to the section of Danté’s 14th Century poem in which Virgil takes Danté through Limbo - that place that is in-between two worlds, not here on Earth and not yet in Heaven or Hell. It is a holding place, in a sense.

This Irish peasant mother and child, as a result of the famine, are struggling in Limbo while on this Earth. They are struggling with poverty, discrimination, eviction, starvation, and disease. This mother is in her own purgatory, not knowing how long this will last, how she can provide for herself and her totally dependent infant child, or how long either of them will survive.

Artist Information:

Liam Ó Broin, born in 1944, lives in Dublin where he began his artistic career at Graphic Studio in 1970. Ó Broin studied tapestry weaving at the National College of Art and Design and won the Scott-Tallon-Walker prize for a woven tapestry, St. Brendan, at the Oireachteas exhibition in 1980. Ó Broin is a founding member of and director of the Black Church Print Studio.

He has divided his creative time and talent over the past 4 decades among various challenges: painting, printmaking, writing, music and photography. Other pursuits of his are poetry and playwriting. He has also acted in productions of The Beauty Queen of Leenane, The Shadow of a Gunman, A Crucial Week in the Life of a Grocer’s Assistant, Give me your Answer Do, and War.

Ó Broin’s works are in the collections of The Office of Public Works, The Arts Council of Ireland, The Butler Collection, Kilkenny and Trinity College Dublin. He has regularly exhibited in group shows at Graphic Studio Gallery Dublin and throughout Ireland as well as Sweden and Australia.

View of Westport House in Co. Mayo from across a lake

.jpg)

Artist: Marquess of Sligo

Date Created: Early 19th Century

Medium: Watercolor on paper

Dimensions: 18 x 22.5 in.

Object #: 2017.5

Piece:

This work, done by the Marquess of Sligo in the early 19th century, shows a charming view of Westport House from across its lake. It is an excellent example of the other side of the Great Hunger. For most of those who were wealthy, life continued throughout the Great Hunger just as it had before and would afterwards. Manors like Westport House were symbols of glittering wealth in Ireland that too frequently rather than providing aid for the starving peasantry, kept up extravagant households and appearances of prosperity and status for their owners. However, Westport House itself is an example of wealth being used for good during the Great Hunger, and the power for change that many of the wealthier in Ireland possessed, whether it was utilized or not.

During the Great Hunger:

Westport House, as its name implies, is situated in the West of Ireland, the hardest hit region by the Great Hunger. At the start of the Great Hunger, Wesport House was closed, presumably to save the cost of its upkeep, and the 3rd Marquess of Sligo George Browne moved into a house in town with his sisters. Even as rents stopped coming in, George Browne spent 50,000 pounds of his own money to help his tenants. He imported food and distributed it so that more people could avoid the workhouse which was the only option for so many. He wrote to the British Government and demanded they do something for those suffering in Ireland. He published ideas for economic reform of the policies that had contributed to the Great Hunger. George Browne was offered the Order of St. Patrick in 1854, a British chivalric order, but rejected it as he had become so disillusioned by Britain’s policies towards Ireland.

Westport House:

Designed in the 18th century by architects Richard Cassels and James Wyatt, Westport House is considered one of the most beautiful of Ireland’s historic homes open to the public. It was the ancestral home of the Browne family until 2014. The Browne family, headed by the Marquess of Sligo, are direct descendants of 16th-century pirate queen Grace O'Malley or Gráinne Ní Mháille. The site of Westport House was once the location of one of Grace O’Malley’s castles, and has had a ‘big house’ on its grounds since that original castle in the 1500’s. The foundations of that castle can still be seen and toured in the basement of Westport House today. The current Westport House was built in 1730 by the Browne family, whose descendants sold the home to local business Hotel Westport in 2017, to better maintain and expand the historic property of Westport House as a tourist attraction.

Artist:

The artist of this work is ambigious, as Marquess of Sligo is a title rather than a specific person. Without an exact date, the best we can do is narrow down the list of Marquesses to the most likely. Given that this work is thought to be from the early 19th century, the most likely contenders for its creator are John Browne, the first Marquess of Sligo, or Howe Browne, the second. The title Marquess of Sligo is part of the Peerage of Ireland, or the titles of nobility set up under the English monarchs following Henry VIII’s conquest of Ireland. Many Irish peers had no connection to Ireland, and titles were given and sought for political gain within the English court and, later, the government of the United Kingdom. Peerage held several benefits, including a seat in the House of Lords depending on the title, a right to be tried by a jury of other nobility instead of a jury of commoners, and freedom from arrest in civil cases.

The World is Full of Murder

Artist: Brian Maguire

Date Created: 1985

Medium: Acrylic on Canvas

Dimensions: 53 x 87 in.

Object #: 2012.15

Through the formal elements of art seen in this painting (line, shape, form, tone, texture, pattern, color, and composition) the viewer feels Maguire’s outrage. The harsh lines, strong colors, and vague allusions to body parts all contribute to the feeling of rage present here.

Maguire’s paintings emanate violence, intensity, unhappiness; the pigment is applied thickly, coarsely, viscerally; the gesturing is aggressive, paranoid, savage; the effect is overpowering, unpredictable, provocative; the physicality is animated, painterly, primeval. In The World Is Full of Murder, reds, blacks and browns are smeared, splattered and striated. The body parts are splayed, foreshortened and fragmented. “What interested me at the time”, he says, “was the physicality rather than the spirituality of the deaths”. It shows a bunch of bodies “mangled—murdered—by their own pathos” beside and on top of each other in a ditch. The absence of a horizon reduces depth, so that the figures seem close to the viewer.

Moreover, Maguire says, the title is pertinent to the Irish Famine, as deaths from hunger, in a world with excess food supplies, is murder. There was enough food available then (and now) to feed everyone, but its availability to the poor is determined by political and economic factors. “Where death from hunger exists in the 21st century, it is a crime committed by all of us who are in secure situations. The Irish experience is mirrored today in the famine experience of the poorest countries. It is the collective memory of 1847 that enables us to hold this gaze on contemporary famine,” he says. The painting has its origins in newsreel footage of Nazi atrocities that Maguire saw as a 12-year-old at his local cinema. It functions on several levels: personal, political, historical. Maguire says “[t]he Irish experience is mirrored today in the famine experience of the poorest countries.”

The Artist:

The Irish expressionist painter Brian Maguire was born in County Wicklow. He studied drawing and painting at the Dun Laoghaire School of Art, and fine art at the National College of Art and Design (NCAD) in Dublin. A gifted student and artist, Maguire was appointed Professor of the Fine Art faculty at NCAD, in 2000.

As a committed artist and visual commentator, Brian Maguire believes in the capacity of art to express political, social and humanitarian concerns. He identifies with the outsider, and engages with the poor and dispossessed, representing them and facilitating their representation of themselves.

Brian Maguire's expressionistic drawings and paintings (as well as his video, photography, and poster artworks) deal with themes of physical and political alienation. His focus on marginalized or disenfranchised groups has led him to work at a number of prisons, hospitals and other institutions in Ireland, Poland, and the USA, including: Mountjoy Jail, Dublin, Portaloise Jail, Spike Island, Co. Cork, Fort Mitchell Prison and Bayview Correction Center, New York. His recent paintings have also been inspired by American and world political events.

Since 2010, the Irish painter Brian Maguire has worked in Juárez, Mexico, creating work in response to the proliferation of deaths that have followed in wake of the Mexican drug war. Maguire’s affinity for social activism stems from his involvement in the civil rights movement of Northern Ireland in the 70s. His large-scale paintings—which utilize wide, open brushstrokes and combine rough, dry marks with vertical and horizontal drips—aim to deny any poetic sensibility to the harsh scenes (dismembered body parts and weaponry) they often depict.

Through observation, Maguire draws attention to marginalized voices. Maguire correlates the place between narrator and voyeur through occupying a role as facilitator, which he is uniquely careful not to exploit.

The Aleppo Series:

In recent years Maguire has turned his attention to the Middle East. In Maguire’s “Aleppo” series, he focuses on Syria’s largest city and the devastation it has seen in recent years. In 2018 Maguire went to Aleppo for the first time to see for himself what had happened to the city during the countries 5-year civil war. He originally made the trip because he believed that the news media was not telling the whole story of how the city had been affected by years of bombing and fighting.

Maguire lived in the city and tried to create relationships with the citizens still living there among the rubble. In 2016, doctors working in Aleppo identified a new traumatic syndrome to describe the people of Aleppo: “human devastation syndrome”, which bolstered Maguire’s belief that the true victims of war are the global poor community. By photographing and subsequently painting the demolished and disintegrating buildings of Aleppo, Maguire chooses to document the visceral physical ravages of war on a city and community.

The paintings show a haunting sense of a city that has largely been left to ruin. They were exhibited at IMMA show “War Changes its Address” in 2020, an article reviewing the show on ArtDaily.com described the work perfectly: “All sharing the title Aleppo, these new paintings are made in a washed-out palette of browns, greys and blues, with the occasional small burst of colour. The uniformity of colour reflects the wiping out of detail and design caused by widespread destruction of the city’s architecture, and the seeming total removal of life from these streets. Rather than a vibrant colourful city, one of the oldest in the world, the viewer is left looking at a place that has been stripped of identity, as well as physically destroyed. The paintings call to mind a stage set, empty after the spectacle of war. The occasional small burst of colour speaks to the unquenchable urge for life to continue, even among the most unpromising of settings.”

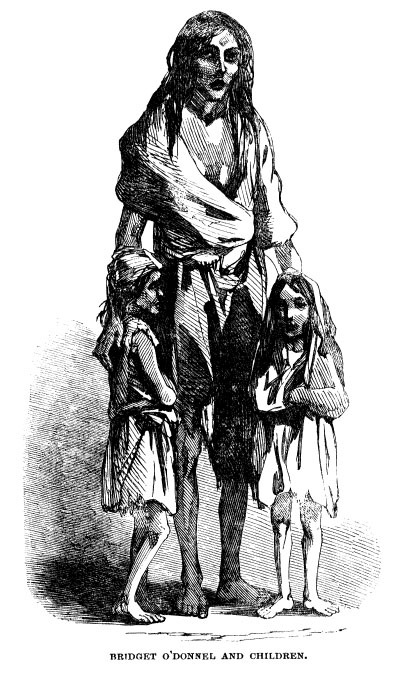

Jane Leary

.jpg)

On display at IGHM.

From the collection of the Skibbereen Heritage Centre

Artist: Toma McCullim

Date Created: 2018

Medium: Bronze on Brick

Object #: 2018.6

The following is written by IGHM docent Maura Stevenson

Artist:

Scottish-born Toma McCullim describes herself as an artist working in ‘participative practice, painter, anthropologist, activist, production designer in film and theatre, and curator.’ She has a BA degree in Anthropology of Art from the University of East Anglia and an MA in Arts Process from the Crawford College of Art and Design, Cork. Now living in County Cork, Ireland, her work has been shown nationally and internationally.

In 2017, McCullim served as an artist in residence at Skibbereen Community Hospital in County Cork, Ireland, which stands on the grounds of the former Skibbereen Union Workhouse. There she would come to know and work with the patients and the staff to complete an art project known as 110 Skibbereen Girls.

Background:

In 1838, the British Parliament passed the Poor Law Act in Ireland. This act divided Ireland into 130 geographical areas called unions. Within each union, a workhouse was built to provide relief for paupers. By the second potato crop failure in 1846, the entire workhouse system throughout Ireland was overwhelmed and the Skibbereen Union Workhouse, which served one of the poorest areas, was disproportionately affected, having been in a deplorable state prior to the onset of the famine.

Admission to workhouses was only granted to the most destitute and families were required to enter as a unit. Upon entry to the workhouses, families were split up according to age and gender – families did not stay together. Because the Skibbereen Union Workhouse served such a large area, some walked 25 to 30 miles only to be turned away. In their state of advanced starvation, they would have to walk back to their point of origin. For those paupers who were granted entry, the rags they wore would be replaced by clothing previously worn by those who had died. Toma McCullim noted that entrants would ‘wrap themselves in tuberculosis, dysentery, cholera and flu.’

By 1847, conditions at the Skibbereen Union Workhouse were extremely poor and mortality rates very high. Records from 1848 indicate that 2,538 residents of the Skibbereen Union Workhouse were under 18 years of age and many of those were orphaned or abandoned.

In 1848, Earl Grey, Secretary of State for the Colonies, implemented the Famine Orphan Scheme which provided for ‘assisted emigration’ to Australia for orphaned girls living in the workhouses throughout Ireland. At that time, there were 9 men for every woman living in Australia and the scheme was viewed as a way to reduce the population in the workhouses and to increase the population of child-bearing females in Australia.

During the timeframe of 1848 to 1850, it was estimated that 4,114 girls, aged 14 to 18 years were sent from workhouses throughout Ireland to Australia. Information gleaned about these girls includes the following. On average, the Irish girls married men 10 years their senior and gave birth to 9 children. One in 15 experienced difficulties in childbirth due to small pelvic structures resulting from malnutrition. Many of the girls were indentured as domestic servants for a specified period and would often go on to marry.

From the Skibbereen Union Workhouse, 110 girls were sent to Australia as part of the scheme and ultimately came to be known as the 110 Skibbereen Girls. One of the documented girls was Jane Leary. She was thought to be 14 years of age when she left for Australia and arrived in Port Phillip in March of 1850 after 3 months at sea. Jane worked as a servant for a while and in 1852, she married Englishman Thomas Constable, gave birth to 9 children and died at 80 years of age.

The lineage of the 110 Skibbereen girls in Australia is estimated to be vast. Toma McCullim and her helpers from the Community Hospital performed some calculations to estimate descendants. With an average of 9 births per girl, that would be 990 direct births from the Skibbereen girls alone. Adjusting for childhood mortality and later, improved health care and contraception, they estimated that by 1968 there would be a total of 14,950 descendants from these girls, spanning 5 generations. Jane Leary alone has many hundred descendants, the youngest now being 7th generation descendants.

The Process:

McCullim asked residents and staff at the Community Hospital each to create a spoon using beeswax. McCullim described the spoon as a basic object that we use to feed ourselves. Among the things that the Famine Orphan Scheme girls would be given for their journey were a bowl and a spoon. A spoon was also one of the objects found during a recent archaeological dig at the Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney, the arrival point for the girls. The spoons were created in groups where family stories would be shared and the lines between staff and patients were blurred through the shared social and artistic experience.

The 110 beeswax spoons were cast in bronze and then mounted on the bricks of the original workhouse wall on the arch of the doorway that led to the section for women. A piece of Australian sandstone, donated by the Australian Embassy, was placed at the foot of the artwork. This tribute is known as 110 Skibbereen Girls.

The Piece:

Separately, a single spoon was cast and placed on a brick from the former workhouse and the resulting piece was named Jane Leary. This piece was gifted to Ireland's Great Hunger Museum in 2018 and is currently on display there.

Sites visited for this information:

https://www.toma-mccullim.com/about-1/

Connemara Girls

.jpg)

Artist: Sir Thomas Alfred Jones

Date Created: c. 1880

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 56 x 44 in

Object #: 2016.7

The following is written by IGHM docent Kathleen McGuire

Artist:

A deserted child whose parentage and exact date of birth were unknown, Sir Thomas Alfred Jones was found and taken charge of by the philanthropic Archdale family who brought him up in their house in Kildare Place, Dublin. His name “Thomas Jones” seems to be borrowed from Henry Fielding’s 1749 comic novel, The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling. The “Alfred” was a later addition, probably by Jones himself.

Showing signs of artistic talent, Jones was placed as a pupil in the Royal Dublin Society’s School in 1833. In 1841, he exhibited a picture in the Royal Hibernian Academy, “Vision of Kings,” a subject from Macbeth. He entered Trinity College in October 1842 but left without taking his degree, went abroad in 1846 and spent about three years traveling on the European Continent. Returning to Dublin, he settled down to his profession as an artist. He sent drawings to the Royal Hibernian Academy in 1849, and from then on became a regular contributor and exhibitor.

His early works were small figure subjects, most of them watercolor or pastel drawings, but he ultimately confined himself to portrait painting in oil in which he achieved great success. His oil portraits are numerous and nearly everyone of note for many years sat for him. Dignified and urbane, he became president of the Royal Hibernian Academy in 1869 and was knighted in 1880, the first Irish artist to be so honored by the British crown.

From the 1860s onward, Jones executed a series of paintings in the “Irish Colleen” genre, featuring wholesome looking young women with gentle, oval faces, wearing domestic, traditional attire.

For some time Jones suffered from ill health, and he died at his Dublin residence on May 10, 1893. He was married twice and is buried at Mount Jerome Cemetery on the south side of Dublin.

The Piece:

Once described in a gallery catalog as “perhaps the masterpiece of the ‘Irish Colleen genre’ of painting, Connemara Girls features three west of Ireland young women with shining hair, lustrous eyes, and exquisitely decorated shawls.” The background landscape shows the rugged, barren terrain of Connemara on Ireland’s west coast, one of those most adversely affected by the Great Hunger. From a birds-eye view, the artist is looking down on a mountain pass dominated by the figures of three barefoot young girls wearing traditional dress.

Bathed in summer twilight, the girls look well fed and happy as they return from gathering some food. The girl on the left carries a basket with bread, turf and a bottle; the girl in the center carries something over her back; while the younger girl on the right clutches what is in her apron with one hand and holds onto her shawl with the other. It was not uncommon for the rural young people of the time to be barefoot.

The viewer’s eye is drawn to the bright red colors of the skirt worn by the girl on the left, the exquisite plaid shawl covering the head and shoulders of the redhead in the middle, and bits of red on the younger girl’s attire. Viewers are also drawn to the wind blowing through the mountain pass as it catches the girls’ clothing and they clutch their shawls against the breeze.

Connemara Woman with Red Skirt

Artist: Seán O’Sullivan

Date Created: 1952

Medium: Oil on Board

Dimensions: 16 x 12.6 in

Object #: 2011.25

Piece:

Seán O’Sullivan’s portraits exude visual vibrancy and are animated and natural.

In Connemara Woman with Red Skirt, O’Sullivan portrays a rosy-cheeked woman from the West of Ireland wearing traditional dress. Head covered and arms folded, she stands full square in front of a lovely landscape. Cottages are sparsely spread throughout the stony land. The low horizon allows for an expansive, cloudy sky above the mountains, which are saturated with iridescent light.

The woman’s red skirt is a trope frequently seen in Irish art from this era, representing women as personifications of wholesomeness, domesticity and authenticity. This trope was derived from the context of the cultural role that was afforded women in the West during this period.

The West of Ireland:

As colonialism and plantation increased in Ireland throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, much of the native Irish population was displaced from the farming land of the East to the rockier West. The West of Ireland became increasingly differentiated from the rest of the country. Marked by its poverty, cultural isolation and geographical inaccessibility, the West came to be seen by many as the real Ireland. It was the repository of Gaelic culture, language and religion. This differentiation gave rise to an iconography of its own, in which we see the association of women with both domesticity and nature.

Artist:

Seán O’Sullivan was born in Dublin in 1906. He was a painter known primarily for his portraits, which featured many prominent figures of the time such as Éamon de Valera, Douglas Hyde, W.B. Yeats and James Joyce. O’Sullivan was raised in St. Stephen’s Green

in Dublin, where his father ran a business as a carpenter and joiner. O’Sullivan stood over 6 feet tall, and was a good boxer, fencer and squash player. He also was an enthusiastic sailor. Well-educated, he was a keen reader and was fluent in both Irish and French. In 1926, O’Sullivan entered the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art, where one of his teachers was artist Sean Keating. O’Sullivan’s attendance was intermittent, but while at the school, he came to the attention of the headmaster George Atkinson, who arranged for him to take a three-month training course in lithography at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London.

While in London, O’Sullivan met and married another young art student, Rene Mouw. The couple spent their early married years studying in Paris. O’Sullivan returned to London in the late 1920s and worked as a lithographer. In the early 1930s, O’Sullivan and his wife moved to Dublin. It was there that he acquired a studio in St. Stephen’s Green. O’Sullivan remained in that studio until his death in 1964.

Working in the city’s center meant that O’Sullivan was well connected within the Dublin social scene at the time. He was on friendly terms with many of Ireland’s best-known writers, actors, poets and painters, including Hilda Van Stockum, Maurice MacGonigal, Harry Kernoff, Patrick Kavanagh, Myles na gCopaleen, F.R. Higgins and John Ryan. Dr. Éimear O’Connor, honorary member of the Royal Hibernian Academy, said O’Sullivan could “turn his hand” to any form of visual art production, from book covers and advertisements to lithographs and large-scale commissioned portraits. Although perhaps better-known as a portrait painter, O’Sullivan also was a keen observer of life on the western seaboard of Ireland. He painted the landscape and the people of Connemara and Kerry, both young and old.

O’Sullivan left a legacy of extraordinary talent. His untimely death in 1964 prompted Maurice MacGonigal, then president of the RHA, to note, “One of the defects of mankind is its failure to recognize genius until it has been removed.” O’Sullivan’s first studio in Dublin at 20 Molesworth Street is home today to the Gorry Gallery.

Mending Nets

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Artist: Howard Helmick

Date Created: 1886

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 21 x 30 in.

Object #: 2011.6

The Artist:

Born in Zannesville, Ohio, Howard Helmick began his art training in the Ohio Mechanics Institute in Cincinnati, and subsequently at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. He would then leave for France and study in Paris at the studio of Alexandre Cabanel at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. He would stay in France until approximately 1870, when he moved to London.

During his time in London, Helmick exhibited at the Royal Academy, the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, the Royal Society of Painters-Etchers and Engravers, the Society of British Artists, and the Royal Society of Artists in Birmingham. He also exhibited his works at the Glasgow Institute of the Fine Arts, the Royal Hibernian Academy, the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool and Manchester City Art Gallery. He was elected a member of Society of British Artists in 1879, and the Royal Society of Painters-Etchers and Engravers in 1881.

Helmick was best known for his oil on canvas paintings that were based on rural Irish life. He developed this preference from his regular visits to Ireland, when living in London. Generally, Helmick would visit the regions of Kinsale, Kenmare, and Connemara. He was the foremost artist among a small set of painters focusing on rural Irish culture, and was hailed by contemporary critics as ‘an American Wilkie.’ His surviving paintings on the peasantry and their houses, priests, doctors, and the arrangement of their marriages give an insight into everyday life in Ireland at the time. His paintings tended to be intricately detailed when depicting the items lying around Irish households, such as the cutlery, the crockery and the flax spinning wheels.

“The Irish are full of weaknesses” he told his American writer friend Julian Hawthorne, “but I like them. Their chief merit is that they are superior to the English.” In Ireland, according to the American critic Clarence Cook, Helmick found “in that land of changing lights and shadows in human life … so many picturesque subjects, [all he needed] to supply the demand for his pictures. It was a field till then almost undiscovered … and [he] was left in almost undisturbed possession of the quarry he had opened.”

Helmick moved to Washington, D.C., in 1887. There he was active in the Society of Washington Artists, the Washington Water Color Club and the Washington Society of Fine Arts. As a Professor of the Philosophy and History of Art, Helmick taught painting and drawing at the Art Students League of Washington, at Georgetown University and in his Georgetown studio. The Washington Post records that while at Georgetown Helmick portraits of all but eight past presidents of the University. He simultaneously exhibited at the national Academy of Design, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Brooklyn Art Association. He was even represented at the Paris Exposition of 1900. Helmick also contributed illustrations to The Century Magazine and Harper’s Magazine and is represented in the Corcoran Gallery of Art and the National Museum of American Art.

Helmick died on April 28, 1907 at his residence in Georgetown, Washington, D.C., at the age of 62. He is buried in Glenwood Cemetery (Washington, D.C.).

The Piece:

“For foreigners, the truth of grinding poverty, frequent famine and substandard housing was veiled by … manipulated images of the ‘dear little cabin,’” at which Helmick excelled, argues Claudia Kinmonth.

This scene here is set in a dark fisherman’s cottage. Two young, barefooted girls chat with their grandfather, while their grandmother sits by the fire. One of the girls sits while disentangling the net, the other hangs the net on a rope from the rafters to dry. The painting is full of traditional items of Irish material culture, such as the Sligo chair typical of Counties Galway and Sligo. Helmick displays his technical skill by rendering different textures: the nets, the flagon and tankard, and the combined candlestick and rush light holder. While the painting suggests that there is much work to be done, the mood is upbeat and lively.

The subjects of fish and famine recur. Of course, there were fishing communities, but they lived precarious lives. The cliffs, rocks and currents rendered long stretches of the Irish coast treacherous. Nets, however, were valuable assets. As we see, making and mending was women’s work. Helmick thus displays not only his artistic skill, but also knowledge of daily family life.

The Victim

Artist: Rowan Gillespie

Date Created: 1997

Medium: Bronze

Dimensions: 9.5 x 8 x 7 in.

Object #: 1999.1

Artist:

Rowan Fergus Meredith Gillespie, known for his distinctive bronze sculptures, was born in 1953 in Dublin. He is unique for his method of creating his work. He takes the work from conception to creation, entirely unassisted. To do the entire process unassisted is very remarkable, and stands out within the bronze casting fraternity.

Gillespie takes inspiration from many sources, one in particular being his grandfather James Creed Meredith, a member of the Irish Volunteers movement. According to Gillespie's official biographer Roger Kohn, Gillespie’s work Proclamation, located across the road from the Kilmainham Gaol in Dublin, was created in memory of both the Proclamation of the Irish Republic and of his Grandfather's dream of a Utopian society.

Gillespie went to boarding school in England at the age of 7, and later attended York School of Art. It is here that he was first introduced to the lost-wax casting process by the bronze sculptor Sally Arnup. This technique was once popular in Europe, but fell out of fashion in the 18th century. Gillespie then attended Kingston College of Art. Following his schooling at York and Kingston, Gillespie completed his studies at the Statens Kunstole in Oslo. He then lectured for three years at the Munch Museum. Edvard Munch, the Norwegian painter, has had a profound influence on Gillespie’s work, both conceptually and manifestly, up to this day.

At the age of 21 he married his wife Hanne, who he met at York School of Art, and they had their first child Alexander. In the same year Gillespie held his first solo exhibition in Norway. In 1977 he returned to Dublin where he set up his foundry/workshop and established himself with Solo exhibitions at the Solomon Gallery in Dublin, Arts Fairs and numerous group shows throughout Europe and the United States. He then decided to concentrate on Site specific art, notably The Cycle of Life, Colorado (1991); The Famine Series, Dublin (1996/7); and Ripples of Ulysses (2000/1). Gillespie’s Famine, completed in 1997 and located in Dublin by the river Liffey, is one of the best known memorials and monuments to the famine in Ireland to this day.

In 2007 Gillespie was awarded an honorary Doctorate in Fine Art by Regis University in Denver, Colorado.

Still living today, Rowan Gillespie continues to work on site-specific commissions, from his bronze casting foundry in Blackrock, Dublin..

The Process:

A master craftsman, Gillespie displays impressive technical proficiency. He uses phosphor bronze for its durability, and employs the complex and labor-intensive lost-wax technique. His singular and often exhausting style involves taking the work through from conception to creation, entirely unassisted in his purpose-built bronze casting foundry at Clonlea, in Blackrock. Working alone is one of the main things that make him unique among the bronze casting community

The following information about the lost wax process has been taken from Encyclopedia Britannica:

“Lost-wax process, also called cire-perdue, method of metal casting in which a molten metal is poured into a mold that has been created by means of a wax model. Once the mold is made, the wax model is melted and drained away. A hollow core can be effected by the introduction of a heat-proof core that prevents the molten metal from totally filling the mold. Common on every continent except Australia, the lost-wax method dates from the 3rd millennium BC and has sustained few changes since then.

To cast a clay model in bronze, a mold is made from the model, and the inside of this negative mold is brushed with melted wax to the desired thickness of the final bronze. After removal of the mold, the resultant wax shell is filled with a heat-resistant mixture. Wax tubes, which provide ducts for pouring bronze during casting and vents for the noxious gases produced in the process, are fitted to the outside of the wax shell, which may be modeled or adjusted by the artist. Metal pins are hammered through the shell into the core to secure it. Next, the prepared wax shell is completely covered in layers of heat-resistant plaster, and the whole is inverted and placed in an oven. During heating, the plaster dries and the wax runs out through the ducts created by the wax tubes. The plaster mold is then packed in sand, and molten bronze is poured through the ducts, filling the space left by the wax. When cool, the outer plaster and core are removed, and the bronze may receive finishing touches.”

The Piece:

The Victim was the first piece acquired by the Museum, and was a gift of the Lender family to help start building the Great Hunger collection at Quinnipiac University. It was part of a series of works commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Famine, executed by Gillespie as studies for the dramatic Famine memorial on Custom House Quay in Dublin. In the memorial, seven larger-than-life figures, and a dog, stagger toward the docks to board the Perseverance, which sailed on St. Patrick’s Day, 1846, landing in New York two months later. The Victim is a quintessential figure, representing each and every one of the millions who died from starvation or disease, or emigrated; its strength lies in its scale and isolation. The scale of the figure contrasts with the scale of the horror. He has suffered pain, loss and humiliation, he sees nothing, hears nothing, utters nothing. As Gillespie says, “My work is figurative; it is about the miracle of human life in a galaxy of indifference.”

A Famine Memorial

Artist: Joe Hogan

Date Created: 2011

Medium: Mixed media

Dimensions: 15 x 20 x 22 in.

Object #: 2011.3

For me nature is an endless source of inspiration. We are fortunate to live in a wonderful landscape. There are mountains, lakes rivers on our doorstep and areas of wild moorland nearby to delight the eye and nourish the soul.

The Artist

Joe Hogan makes new objects from old materials. He has been making baskets at Loch na Fooey, County Galway, since the 1970’s after graduating from the University College Galway with a degree in philosophy. He was attracted to the craft because it offered the possibility of involvement in the whole process, from growing the willow through to making the finished object. One the attractions to this craft for Hogan was the fact that you could grow your own raw material. “I was drawn to basket-making because willow growing provided an opportunity to live rurally and develop a real understanding for a particular place. Over the last thirty years, I have found it a very satisfying occupation. You learn to be patient, to work in the present moment and to not prejudge the outcome.”

In addition to creating his own works, Hogan also teaches and demonstrates basketmaking. He also was the co-curator of the 'European Baskets' exhibition, which was held in association with The Crafts Council of Ireland in 2010.

His interest in indigenous baskets led him to write three books on the craft, “Basketmaking in Ireland” (2001), “Bare Branches, Blue Black Sky” (2011) and “Learning from the Earth” (2018). Since 2000, Hogan also makes non-functional baskets using twigs of birch, bog myrtle and other found material from a bog near where he lives. Some of his most recent works are from wood fragments, which bear the marks of the lifetime of the tree, providing a starting point for the story that he weaves.

The Inspiration

The following is from “Bare Branches, Blue Black Sky” (2011) by Joe Hogan, which was release in conjunction with his exhibition at the Garter Lane Gallery in Waterford, Ireland.

“It’s no metaphor to feel the influence of the dead in the world, just as it’s no metaphor to hear the radiocarbon chronometer, the Geiger counter amplifying the faint breathing of rock, fifty thousand years old. (Like the faint thump from behind the womb wall.) It is no metaphor to witness the astonishing fidelity of minerals magnetized, even after hundreds of millions of years, pointing to the magnetic pole, minerals that have never forgotten magma whose cooling off has left them forever desirous. We long for place; but place itself longs. Human memory is encoded in air currents and river sediment.”

-From “Fugitive Pieces” (1998) by Anne Michaels.

I look across at the traces of potato beds dug by spade more than 150 years ago and wonder about the people who lived here then and the suffering that was endured in the great famine. These ideas by Anne Michaels from her wonderful novel, “Fugitive Pieces”, inspired me to try to make a commemorative basket of some sort. I plan to return to these ideas again as a source for other work.

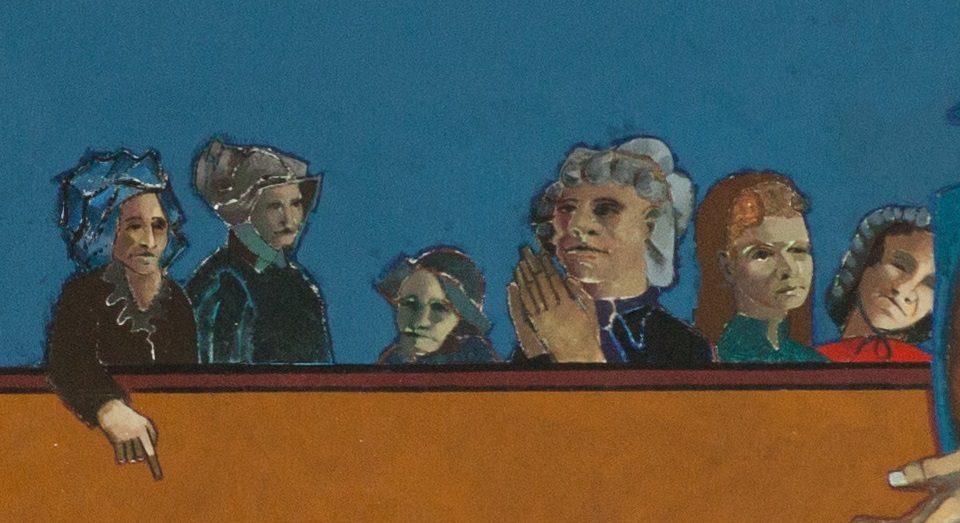

Pilgrims to Clonmacnoise Cross, County Offaly

Artist: Francis William Topham

Date Created: c. 1845

Medium: Watercolor on paper

Dimensions: 11 x 18.5 in

Accession #: 2018.3

Piece

This work by British artist Francis Topham shows a group of pilgrims at the base of a large stone cross at the monastery of Clonmacnoise.

The location of this work is significant - the monastery of Clonmacnoise is a site of pilgrimage with a tradition stemming from the 6th or 7th century and continuing today. Clonmacnoise is found in County Offaly in Ireland, on the River Shannon, and was founded in 544 by St. Ciarán – one of the Twelve Apostles of Ireland. Many of the high kings of Tara and Connacht were buried at Clonmacnoise.

Artisans from the community surrounding Clonmacnoise created some of the most beautiful and enduring metal and stone artworks ever seen in Ireland.

The cross featured in this work is the Cross of the Scriptures. It is 4-meters-high and one of the most skillfully executed of the high crosses that survive today in Ireland. It is particularly noted for its inscription, asking a prayer for Flann Sinna, King of Ireland, and Abbot Colmán who commissioned the cross. The cross was carved from sandstone taken from County Clare. The three distinct sections of the body of the cross show the Crucifixion, the Last Judgement, and Christ in the Tomb. The Cross of the Scriptures remains one of the steps in the modern day pilgrimage tradition.

Clonmacnoise Monastery

Clonmacnoise was founded in 544 by St. Ciarán – one of the Twelve Apostles of Ireland. The monastery is near dead center of the island of Ireland and Northern Ireland. Many of the high kings of Tara and Connacht were buried at Clonmacnoise. The original buildings that comprised the monastery were made of wood, and were replaced with stone in the 9th century. The monastery faced many challenges in its existence including a bout of plague in the 7th century and frequent attacks by Vikings, Normans, and 27 times by the Irish themselves. Pilgramage to Clonmacnoise is a tradition stemming from the 6th or 7th century, and continued even today. Pilgrims come to celebrate St. Ciarán on his feast day.

Artist

Francis William Topham, watercolor painter, was born in Leeds, Yorkshire, in 1808. He was taught to engrave through an apprenticeship with his uncle, Samuel Topham. In 1830, he moved to London to take up heraldic engraving before joining the publishing firm of Fenner and Sears as an engraver of title-pages and illustrations. This led to original illustrative work for books, and for the Illustrated London News, and in 1851 he contributed engravings for the three volumes of Charles Dickens' A Child's History of England.

In March 1832, Topham married was married to the sister of a fellow engraver, Mary Anne Beckwith with whom he had numerous children. His eldest son, Francis William Warwick (Frank) Topham (1838–1924) would also become a painter, and married Helen Lemon, daughter of Topham’s friend, Mark Lemon, the first editor of Punch in 1870.

In London, Topham joined the Artists' Society for the Study of Historical, Poetical and Rustic Figures. The society met to draw models picked from street vagabonds. It was also at the Artists’ Society that Topham was recruited by Charles Dickens to join his amateur theatrical company, the Guild of Literature and Art. In addition to appearing in London, provincial theatres and several country houses, he frequently performed with Dickens before Queen Victoria.

Despite his foray into theater, Topham continued to paint and soon chose peasant life as his favorite subject. Topham’s earliest works were of peasants from Wales and Ireland. He began to exhibit in 1832 and had seven paintings shown at the Royal Academy. In 1842, he was elected an associate of the New Society of Painters in Water Colours, becoming a full member the following year.

In 1844, Topham visited Ireland for the first time, alongside fellow artists Frederick Goodall, Alfred Downing Fripp, and (Henry) Mark Anthony. While the work that Topham produced on this trip was in the sentimental style, these pieces are some of the only visual records of conditions in Ireland before and during the famine. Topham and the rest would return to Ireland together several times, making records of progressing conditions within their charming rustic scenes.

In 1877, Topham, whose health had been failing, took ill on a journey to Córdoba in Spain, which he had visited many times before. Topham collapsed soon after arrival and died on March 31, 1877. He was buried in the protestant cemetery outside Córdoba. When that fell into dereliction he was reinterred, in 1959, in the municipal cemetery of San Rafael, where, in 1994, a nearby square was renamed plaza del Pintor Topham in his honor.

Examples of his work are in the collections of the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, the Williamson Art Gallery and Museum, Birkenhead, Bury Art Gallery and Museum, Reading Art Gallery and Museum, the Ulster Museum in Belfast and the municipal collection in Córdoba.

The Finishing Touch

Artist: James Brenan

Date Created: 1876

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 25 x 30 in

Accession #: 2011.4

The artist:

James Brenan was one of the most influential figures in the history of Irish art of the 19th century. Born in Dublin, he studied at the School of Art in Leinster House, the Royal Hibernian Academy School and the Royal Dublin Society school of drawing, before leaving for London to continue his education. In 1857 he trained as an art teacher and taught at the Birmingham School of Art. Brenan was appointed headmaster of the Cork School of Art in 1860, at the age of 23, where he would stay for the next 29 years. He was a member of the Committee of the Cork Exhibition in 1883, and had charge of the fine art section.

In 1889 he was chosen as Head Master of the Metropolitan School of Art (now the National College of Art & Design) in Dublin. In this role he played an important part of the development of the school and the advancement of crafts and industrial art throughout Ireland, especially lace-making.

Brenan had numerous pieces of his work on display at the Royal Hibernian Academy between 1861 and 1906. He was elected as an Associate of the RHA in 1876, and a Member in 1878. Most of Brenan’s best work was set in cabins or farmhouses, where he returned repeatedly to socialize with farmers, weavers and fishermen, and use them as his models and their homes as his backdrops.

The piece:

In The Finishing Touch, James Brenan explores post-Famine conditions in Ireland. Here a father rests his hand on his daughter’s travel box. As he looks on, the local sign writer carefully paints her name and destination on it. While there are few paintings of the Famine contemporaneous with the Famine, Brenan’s paintings are highly informative of post-Famine conditions, and illustrative of the ongoing struggles of a country that continued to be ravaged by poverty and emigration.

Traditionally, emigration paintings were set on quaysides; Brenan’s emigration scene, then, is all the more poignant for its homely setting. The Irish cottage negatively connoted poverty and primitivism, but also positively traditional family and community values, albeit dented by decades of famine, eviction and emigration.

The painting shows a young woman preparing to emigrate to America. The local sign writer, sitting on the “creepie” stool, is inscribing her name and destination, “O’Connor, New York”, on her modest travelling box. The box was typically small enough to be carried under one arm, and to contain only the most essential possessions for the hazardous journey across the Atlantic.

The young woman’s infirm father, with heavy heart, places his hand on his daughter’s box. And he knows that his young son, carrying the turf into the kitchen in a creel on his back, will be next. The grandfather sits morosely by the fire. Usually it was the young, and even children, who had to go. Their parents and grandparents and youngest siblings, without job prospects or the means to travel or resettle, were forced to stay behind.

Dr. Claudia Kinmonth states that “Brenan’s title, The Finishing Touch, refers not only to his hand on the emigrant’s box, but also to the work of the painter, who is completing the words on the green box. The green is of course symbolic of Ireland. Brenan was also concerned with the poor state of Irish schools (another topic that he addressed through his art) and the sign-writer, seated on a four legged creepie stool, has struggled to form the letters of the girl’s name O’Connor, New York.”

On the back wall, Brenan has included a small broadsheet with an image of the Madonna on it. Luke Gibbons, Professor of Irish Literary and Cultural Studies, notes “A picture of the Madonna, mother and child, is juxtaposed against mother and child in the kitchen. The mother’s comfort is from the next world; the Madonna. But her daughter’s comfort is from the New World.”

Post Famine Emigration in Ireland:

Between 1850-1913 over 4.5 million people left the shores of Ireland to begin a new life. Roughly one in two people born in Ireland in the nineteenth century emigrated. In the late nineteenth century, nearly as many people born in Ireland lived outside the country as lived in it.

Luke Gibbons states “That's where the phrase comes from, ‘the Sea-divided Gael;’ that half of Ireland is elsewhere. This notion of the importance of elsewhere, that to be an Irish person is always to be aware of somewhere else, seems to be part of what the immigrant ethos means. That immigration wasn't just a social event; it was a mentality. And part of the mindset of Irish people.”

So many left for America that a tradition known as the “American Wake” began. The “Wake” was a gathering for friends, family and neighbors, on an emigrant’s departure. It was a chance for one last goodbye. In most cases the event usually began at night, but was often a somber occasion.

Rainbow's End

Artist: William Crozier

Date Created: 1965-1970

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Dimensions: 71.7 x 47.8 in

Accession #: 2015.6

Artist:

William Crozier was born in Glasgow in 1930 the son of working-class Scottish and Irish parents. The combination of these cultural inheritances greatly influenced Crozier from a young age. Crozier studied painting and drawing at Glasgow School of Art from 1949-53 and on graduation left behind the restricted possibilities of art in post-war Scotland, setting off for England and then to Paris, where he would immerse himself in existentialist philosophy, art, and politics. Later he spent time in New York City, but it never felt like home as much as Europe.

From his earliest years, and influence from his parents, Crozier thought of Ireland as his spiritual home and in the mid-1950s he lived in Dublin, scratching a living painting theater sets and forming close friendships in Dublin’s literary circles. In 1954, he married Elspeth McKail, an actor, and later they had two children. In 1965, he and Elspeth divorced. In the mid-1970s, he met and married art historian Katharine Crouan.

William Crozier died of cancer, peacefully in his own home in 2011, at the age of 81. His work can be seen in the collections of many institutions, including the Tate Gallery, and the National Gallery of Ireland.

Style: